I believe all biblical scripture is inspired and useful for our learning, even though the conclusions I draw from their writings have evolved as I get older, acquire more knowledge, and (I hope), mature in the faith. I understand that it’s my understanding of Scripture that has evolved, not Truth. Truth is not relative, but our fallible understanding of it is; which is why our opinions about Truth can and should evolve as we gain years and wisdom. If they don’t, we’re not growing as Christians.

So when we anchor Biblical truth in our minds by some past popular understanding of it–whether so-called “historical Christianity,” or the teachings of the [church/sect/cult] we grew up in—we are risking measuring ourselves by ourselves. We are putting our faith in some man or woman, or some fallible line of reasoning, or some verdict from a May Meeting, in order to get around what the Bible clearly says.

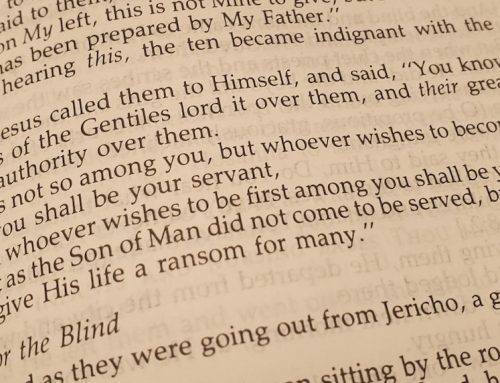

I think the guidepost for the Christian faith should not be the opinions of the church we grew up in, or the church that first brought us into Christianity, or some really smart person we trust—but the Bible itself. We should not be anchored to human opinions, not prevailing opinions of really smart people or even this blog. We are anchored to God alone, and his revealed Word found in the text of the Bible alone. If I contradict your understanding of scripture, then follow your understanding of scripture. But don’t confuse scripture itself with your understanding of it. We all have to reserve some humility and acknowledge that our understanding of scriptural truth grows over time. That’s why it’s so dangerous to bind our opinions at any given point in our growth on others.

In the history of Christianity, the idea of giving authority to the Bible alone has been called sola scriptura, or scripture alone. It simply means that there is no other source that is authoritative in faith or practice. Not a denomination, not a single church, not a single person. Where a person’s, or church’s, or denomination’s teachings contradict what the Bible says, we have to be courageous enough to trust the clarity of God’s word over someone else’s opinion of it. That may be easy, or that may be hard, depending on the topic. But as believers, we have to retain that kind of radical independence from human institution—or shall we say, radical dependence upon the Word of God. This takes a level of self-awareness that many don’t have, or haven’t yet learned.

Prevailing opinions have changed dramatically over the two millennia that have passed since Jesus walked the earth. We have had numerous fads in hermeneutics, theology, Christology, and eschatology come and go. There is Gnosticism, Arianism, Docetism, Humanism, and dozens of others philosophical or systematic theology fads that Christians over the past two millennia have gotten caught up in. We have thousands of denominations come and go, each claiming its own “distinctive” raison d’etre.

I personally believe the doctrine-du-jour of a premillennial rapture is a modern fad. By most accounts, it did not originate until the 18th century, and wasn’t popularized until the 19th century. If “orthodoxy” or “historical Christianity” are our guides, this teaching ought to have been met with suspicion, or at least examined more rigorously in light of scripture when it first arrived on the scene. Yet here we are, over 200 years later, and premillennialism seems to be the dominant opinion in pop-Christianity.

This is not to say that prevailing opinions within modern Christianity and what we call “historical Christianity” should be taken lightly. To the contrary, we should take seriously any departure from how our brothers and sisters in the Christian faith currently understand the scriptures, and how they have historically understood it for the past 2,000 years. But preserve fallible opinions in a glass box to be worshiped for all time? Sorry, I’m not going to go there, whether that glass box was created in 325 (First Council of Nicaea), 381 (First Council of Constantinople, 431 (First Council of Ephesus), 451 (Council of Chalcedon), 553 (Second Council of Constantinople), 680-681 (Third Council of Constantinople), 787 (Second Council of Nicaea) or at last year’s May Meeting.

We should certainly learn from the viewpoints of those who have gone before us. But we shouldn’t take those viewpoints—either individually, or in composite—as the last word to define acceptable boundaries in our faith. The last word should be the Word itself, and I think that is a precept we have to all unite around, if we are ever going to unite per Jesus’ prayer. But it’s only when you come to disagree with prevailing opinion that this thesis gets truly tested. It’s easy to agree with the right to dissent when you’re in the majority with the popular thinking on a subject. When you’re in the minority, it’s a bit harder.

So what do you do when you’re in that dreaded minority? Do you stick with your principles and vocally hold up the Bible above the opinions of men, even if that means you stick out like a sore thumb? Do you go on the offensive, trying to drop self-styled “truth bombs” on the world, thinking that will convert them? Do you conform to the masses, and assume God would not allow the majority to be wrong for 2,000 years of church history?

What principles do you sacrifice? The ones that say you can only associate with those who are as righteous, and as correct as you? Or the ones that say to love your neighbor even if he’s wrong, with the goal of persuading him of his error?

By now, maybe you’re a little uncomfortable with where this is leading. And you should be, frankly. The possibilities of where one could be led by the slippery slope of truth-seeking, stripped of the peer pressure of our friends and associates in “churchianity,” should make anyone a little uncomfortable. We shouldn’t be flippant, after all, about parting ways with the many wise and honored contributors to Christian thinking of the past two millennia, the past two centuries, or the past 48 years. Yet you may be surprised to learn that the inspired authors of the New Testament scriptures believed some things that would be heretical to moderns. Were they wrong, or are we? Hmmm, I wonder.

Leah Remini has been doing interviews to expose the Scientology religion for the cult that it is. There are many similarities between Scientology doctrine and that of the SCOC. She talks of being bound in the prison of her own brain- being the reason she didn't leave it sooner. I would encourage everyone to watch this on UTube. A&E channel also featured Scientology on its channel the other night. Their cult also teacher that its members are to "REPORT" on each other when someone offends the doctrine. Please watch this.

Yes Donna it is amazing once you step back and look at the methods and tactics of other religions that you start seeing patterns. The only exposure I ever had to cult behavior was in Nov 18, 1978 with the death of Jim Jones and the peoples temple in french Guianna. I thought how can people be such fools to believe in this man? Then I was drawn into the Stanton church of Christ and was told that I had found "the truth" yet two week in, the teaching preacher started yelling at me from the pulpit for asking a… Read more »

I had watched a bit of her interviews but it was so sad I could not believe it. Now I find similar things have happened in my own family. It makes me sick to my stomach. I know my grandchildren were taught good things and manners and respectful to adults and have good friends but I pray they do not stay with this cult and get out. Looking back as to why they could not do so many things and why they could never miss a bible class or church unless very sick even when they were exhausted and needed… Read more »

Yep as Donna points out the Scientology religion being exposed so does Merie's cult. When you cannot ask the evangelists what their support is I see as what are they hiding? Really they are no different than payed preachers these days. Portland hasn't had a visit from either one now in almost 8 years, Portland has been leaderless for 19 years. They've gone from so called evangelists to payed preacher dictators