Stanton has altered the meaning of so many words, it’s hard to keep track; hence the new glossary. One of the terms that has been severely misused is the word “prove,” as in “prove all things.” I’m not saying that the word is always misused, because I’m not there to know. But it’s apparent that it’s at least misused when it’s convenient. The following is a portion of a talk at the Labor Day 2013 meeting:

“We put a lot of stock in you brethren that are very, very young in faith. Very young in faith. We put a lot of hope in you, that not only are you going to be able to carry the mantle, you’re going to turn around and you’re going to improve what it is that you have learned. Not disprove, and not try to challenge it, or turn around and make it so where it is you find that it’s false, and its flaws and its errors, but to where it is that you prove it, and strengthen it and strengthen it and strengthen it. You hear in my voice I’m passionate about this. I’m very passionate about it.”

The speaker goes on to talk about how young Christians would be tested by challenges to things they’ve been taught (by this blog, perhaps?), but they are apparently not supposed to subject their teachings to any sort of test at all, not even to the point of getting answers “to their own satisfaction.” They are to accept whatever level of understanding God has granted them and put aside the rest:

“It’s got to be what God has granted you to understand, to his satisfaction, and he may only give you just so much. And so much, that you must develop a faith around what it is that he reveals and conveys to be able to sustain you and how you may be able to endure as well as how you may be able to continue to respond.”

This teaching is downright dangerous, because it teaches new converts and old to set aside their own critical thinking that God gave them, and let others do their thinking for them. I would suggest that subjecting what we’re taught to the scriptures “to our own satisfaction” is exactly what God asks and demands. In fact, to accept something that is not “to our own satisfaction” is a violation of our conscience.

Doing this repeatedly sears our conscience and trains us to rely on our teachers’ regurgitation of the Word rather than our own processing of it. How is that any better than Christians who rely on whatever their pastor says in the sermon on Sunday morning? Short answer: it’s not. It’s accepting the doctrines of men based on their own human authority. By contrast, testing what we’re taught against our understanding of scripture is exactly what the Bereans were commended for.

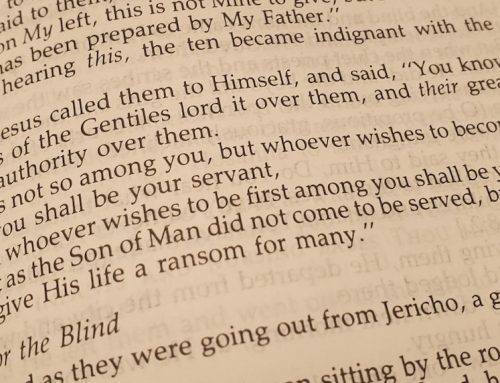

With that in mind, let’s look at Paul’s instruction to “prove all things:”

1 Thessalonians 5:20-21 – Despise not prophesyings. 21 Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.

In proper 17th century usage (when the King James translation was published), “to prove” meant “to test.” If you were to prove a horse, it was not to offer an irrefutable argument as to why the horse was a horse, so that no one could deny it, but to test the horse to find out its capabilities. If it didn’t meet up to your requirements as a beast of burden, for instance, you could decide not to buy it.

It’s with this meaning of the word in mind that King James’ translators correctly chose the word “prove” to translate 1 Thessalonians 5:21. To set the stage even further, we have to understand that some in the first century had a spiritual gift of prophesysing—in other words, a gift of publicly speaking the words, or at minimum the ideas, given to them by the Holy Spirit. The tricky thing was that not everyone who had the gift of prophesying also had the ability to perform miracles to “prove” (modern usage, to offer convincing arguments) they were speaking by the Spirit. Therefore, some might claim they had the gift who really did not.

Paul’s instruction, interestingly enough, was to ask the hearer, not the teacher, to “prove all things.” Test it. See if what this person is saying holds up to scriptural scrutiny. The burden of “proof” (modern usage) may have been upon the teacher, but the responsibility to “prove” the teaching (archaic usage, to test) was upon the hearer.

This is simply a case of words changing meanings over time. Yet the correct meaning of the verse is still very apparent. Paul is saying to “test” all things and hold onto the good parts. This necessarily means discarding the bad parts. By this we know that some of what they would be taught would be good, and some of it would be bad. That’s why they were supposed to test it, discard the bad, and keep the good.

So let me ask you: if the first century church was expected to evaluate the teachings they were hearing, and they had people walking around who were able to prophesy miraculously by the Spirit, shouldn’t we all—Stanton members included—be expected to do the same? Is it too much to ask that every believer prove, i.e. test, the teachings they hear against the Word itself? Or are Stanton’s teachings somehow exempt from scrutiny?

It makes a mockery of Paul’s words if we distort them as if he’s saying to “prove” the teachings of the church to oneself, repeatedly trying to offer yourself convincing arguments to keep yourself on board with the prevailing teaching du jour. That’s the opposite of critical thinking. It’s the opposite of proving all things and holding fast that which is good. Paul was not interested in producing a crop of young Christians trained to blindly follow their leaders. He wanted young Christians who were willing to think for themselves critically and discard erroneous teaching before it could establish itself in the first century church.

I’ve never asked anyone to accept my opinions without scrutiny. All I’ve ever done on this blog is ask my readers to test what they read here, and discard what they can’t find in scripture. May Stanton’s teachers one day be bold enough to do the same.

Excellent post Kevin! Taking a deeper look into what was actually taught at this Labor Day event it is very revealing. How does one “improve” on what you have learned according to scripture other than by improving oneself by obedience to the Word of God? You can’t improve the Word of God because His Word is perfect and will remain so. You can put to the test the Word of God all day long and it will remain true. The only time falsehoods, flaws and errors enter in are when you add and take away from His Word by instituting… Read more »

I agree with Anonymous 7:36 – Excellent post! Thank you and God bless you.

I agree, another excellent post. I thought the same thing as I listened to the Labor Day talk. Stanton CoC's definition of prove is to memorize church doctrine and to review it as often as necessary to have a strong belief in it. Another impression I got was the speaker (and this seems to be a Stanton CoC belief) that it is more important to hold on to your pride (of being the only true church) than it is to possibly consider that church could be wrong.

Thank you for your post Anon 7:36. I agree with your post as well.

Anon 7:36, I thought the same thing about the "improving" comment, that seemed a little bizarre to me. And yes, tradition is exactly what all these rules and regulations are. You certainly can't find them in scripture.

Exactly, Wendy. Their doctrine that they alone are the one true church is central to their entire culture, and it must be protected at all cost, it seems.

The Jewish media, schools, corporations, and victim groups say all races can live together, and it’s loving and peaceful, and anyone who disagrees with this is “racist.” But if that’s the case, why are they hiding the horrific crime statistics? Why are you unable to Google rape, murder, and violent crimes by race for nearly any big city in America? Chicago, Detroit, San Francisco, Oakland, Atlanta, Denver, Dallas, Houston? How come? It’s because the Jewish bankers know that if we all knew the crime statistics we’d begin to question their diversity narrative. We would question why they are trying to… Read more »

Here are some of the annual statistics for the years 2001-2003 (keep in mind that Whites represented 72% of the population at the time and blacks about 13%): There were almost 770,000 interracial violent crimes committed between blacks and Whites Blacks committed 85% of those crimes Blacks committed 39 times as many violent crimes against Whites (roughly 650,000) as vice versa Blacks robbed 136 times as many Whites (139,000) as the reverse Blacks raped 17 times as many White women (15,400) as the reverse (This number is certainly much higher, White men almost never rape black females. It is probably… Read more »

Part 1 God is a God of truth. Without truth, there can be no love or unity. Love or unity without truth is simply deception, and the people who do this are living a lie. It is a terrible existence to sacrifice truth for unity. No one in the Bible who was righteous did it. Or if they did, they risked severe consequences, such as Abraham twice lying about Sarah and saying she was his sister, and Isaac doing the same thing with Rebekah. Or Peter denying Christ. So, God looks upon all humans and races equally. His law applies… Read more »

KALERGI PLAN: What everyone needs to know Article on my website, 12/22/23 After publishing the book, Kalergi received help from Baron Louis de Rothschild who put him in touch with one of his friends, banker Max Warburg. Warburg then supported Kalergi with considerable funds to help form his European movement. The main problem lays with the fact that what Kalergi called for was not only the destruction of European nation states but also the deliberate ethnocide of the indigenous, mostly Caucasian race of the European continent. This he proposed should be done through enforced mass migration to create an undifferentiated… Read more »

KOL NIDRE: THE JEWISH VOW OF DECEPTION It’s important that you learn this so that you’ll face 2024 equipped with even more knowledge about the enemy of God, the enemy of God’s only Son, and the enemy of all those who love them. The Kol Nidre is a Talmudic doctrine of deception, and the “holiest Jewish prayer”. It’s recited several times on Yom Kippur, the “Day of Atonement”. Kol Nidre means “All vows” and is a flat statement that no promise of any kind will be kept for the coming year. So, they are literally saying that they will lie… Read more »

The old gray mare

She ain’t what she used to be

Jack and Jill went up the hill

To fetch a pail of water

Jack fell down and broke his crown

And Jill came tumbling after

Mary had a little lamb

It’s fleece was white as snow

Everywhere that Mary went the lamb was sure to go

Followed her to school one day

Which was against the rules

Green Acres is the place to be

Farm living is the life for me

Land spreading out so far and wide

Keep Manhattan, just give me the countryside

Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way

Oh what fun it is to ride in a one-horse open sleigh

Peanut butter and jelly

Bologna and cheese

Tuna salad

Grilled cheese

Zippety doo dah zippety ayyyy

My oh my what a wonderful day

January, February, March and April

May, June, July and August

September, October, November and December

That the best you can do?

You disagree with ideas you don’t understand and your solution is to holler gibberish?

There is massively disproportionate feminine influence on the vast majority of men in America, and this has crept into the church.

Notice how she doesn’t say she is teaching men in Bible classes. She is so busy fulfilling the role God designed for her, and she trusts God, she doesn’t have time to waste trying to publicly teach with men present.

Pretty funny. Your response is so typical. If I had to guess, I’d say you were a woman. This is how most women respond to uncomfortable truths, though there are effeminate men too. Stanton has often called critics “crazy” and said “they have lost their minds.” This despite many being correct and telling the truth. Plugging your ears and saying “La, la, la, la,” is not how you convince others of your point of view. Dozens of other emotional commenters on here in the last decade. They are all gone; you will be too soon, as logic always destroys emotions.… Read more »

J*wis* pornography and the decline of the west. part 1

Article on my website,

12/24/23

Sad this website allows someone to post 20+ comments of assorted gobbledygook, but often censors long, well reasoned posts.

Can’t even say the ethnicity of the problem race, or the comment is often censored.

Great book by E. Michael Jones

Shows how sexual subversion is used to weaken men and destroy nations for Jewish domination. Been happening for centuries.

Normally don’t watch movies, and I may never watch it again, but “It’s a Wonderful Life” just may be the best film ever made. Know why Mary had so much time to devote to her husband through all his failures, and to her children? Because Mary wasn’t spending time trying to excel in a sphere God didn’t design for her. Mary wasn’t speaking in the churches. Mary was a far better example of a Godly woman than Merie Weiss. Mary in “It’s a Wonderful Life” is a perfect example of a godly, submissive wife. When she and George first became… Read more »

Who are the women from the Bible we remember? Do we remember any women who publicly taught in assemblies of men? We sure don’t. Even Deborah knew she was out of her place and eagerly sought Barak to assume the leadership, We remember Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, and Leah. Why? Was it because they had perfect husbands who were worthy of obeying? Not really. All of their husbands had problems with cowardice, deceit, and sometimes outright lying. It was because they all submitted to a perfect God by submitting to their imperfect husbands. We even remember these Godly women when they… Read more »

Marie is an example of what will happen to women teachers long after they leave this earth. She had a charisma and righteousness that was unmistakable, and yet, her heart wasn’t perfect in one area. She did not obey God’s command to not speak in the church. And so now, 43 years after she passed, her mistakes are gradually coming to light, and it will tarnish her legacy. What good is it if we get people to admire and like us when we are alive, but after we die, our disobedience to God’s order is revealed, and it’s shown that… Read more »

Without true freedom of conscience, leaders cannot lead, they can only enforce.

They become tyrants lording their own consciences over their subjects, whether intentionally or not; whether maliciously or not. This is indisputable when church members have no freedom of conscience of their own to form their

own opinions. They must submit to the opinions of their superiors.

Yes! Two thumbs up!!!!

That’s well said. This scripture was used a lot, and it’s true. However, it means to obey men as they obey God, not one step further. That means one needs to learn and apply God’s law themselves and not be afraid to stand on God’s truth, even if every church leader disagrees with you. However, be sure you aren’t deceived or deluded before you do this, or you are truly lost. Misplaced confidence is destructive, and the graveyard of history is littered with the bones of those who foolishly opposed righteous leaders on matters the rebel little understood. Above this… Read more »

True. It’s unfortunate Stanton doesn’t have elders in each congregation but they have a man and often a woman who rule over the congregation. If a man isn’t worthy of eldership what makes him worthy to run a church.

If a man can’t run his marriage, and no man in the Bible ran his marriage in a church where women spoke publicly, as that didn’t exist in the NT, how can he run the house of God? As soon as Paul finishes teaching women to remain silent in the churches, in 1 Timothy 2 [11] Let the woman learn in silence with all subjection. [12] But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence. [13] For Adam was first formed, then Eve. [14] And Adam was not deceived,… Read more »

1 Corinthians 14 [34] Let your women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to be under obedience, as also saith the law. [35] And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at home, for it is a shame for women to speak in the church. God says it is a shame for women to speak in the church. What shame is he speaking of? Well, if they have children, their children are often getting into shameful things when their mother is in a sphere… Read more »

One of the reasons why God commanded women to stay silent in the churches was because it’s extraordinarily difficult to put the cat back in the bag when it’s out. How do you publicly tell a woman she’s out of her place and needs to remain silent in the church as God commanded? As any man with common sense knows, you don’t do this if you wish to avoid a massive firefight. And the women who speak in the churches have a host of excellent and likeable qualities. If I went just by my senses and not by God’s word,… Read more »

Same Jewish MoneyChangers from the New Testament are hard at work today. Moneyprinting: Moneyprinting is wealth redistribution from the general public (and the poor) to the bankers. By printing more currency and growing the money supply, all the existing currency is devalued. At the time of printing, the bankers and government can use the money at the current rate. It is literally robbing the money out of your wallet. Every dollar that is printed is stealing value out of the money you already have and giving it to the bankers (in national debt interest) and the government. Moneyprinting is the… Read more »

What are your feelings on eating meat? Adolph was a vegetarian.

I’m an omnivore. I’m uncertain about Adolph. Definitely, the Allies were run by Jewish bankers. It’s possible he was too—too many question marks. However, it’s certain that the Holocaust either didn’t happen to the extent we are told or may not have happened at all. There is evidence the gas chambers weren’t built until after World War 2. Also, Eisenhower, Churchill, Truman, and Clemenceau didn’t mention anything about gas chambers in their memoirs. Ernst Zundel actually endured two trials in Canada, in 1985 and 1988, and was finally acquitted in 1992 for publicly questioning the Holocaust. Free speech gives the… Read more »

That was a rhetorical question. As you have given yourself over to doctrines of devils and now, the seducing spirits of entertainment; the forbidding of eating meats cannot be far off. So, you vilify media as evil but then watch “it’s a wonderful life?” Are you not a hypocrite? You fail to follow your own advice; one has to wonder what other media you have been watching. In the virtual world one can be a superhero, or a super villain, or a super lover and all the vicarious entertainment only serves to deceive oneself. Reality hits hard when the fantasy… Read more »

I watched “It’s a Wonderful Life” nearly twenty years ago, long before I learned who controls the media. Isaiah 29:21 That make a man an offender for a word, and lay a snare for him that reproveth in the gate, and turn aside the just for a thing of naught. Isaiah described you well over 2,500 years ago. Imitating what you saw done in Stanton, you furiously and emotionally flail, seeking to catch a weak point. This is why it isn’t safe for anyone to be vulnerable in Stanton; there are often tyrants like you who try to use others’… Read more »

((((Herb Kohl))))) passed away. He was a U.S. Senator, the owner of the Milwaukee Bucks, and owner of Kohl’s Department store.

His tribe is massively over represented among professional sports teams owners.

Humans all have lust and envy in them, but it’s tremendously inflamed when one tribe prints out hundreds of trillions for themselves and their friends; and leaves the rest of humanity nearly destitute.

Any of us could be a hard working success story like Mr. Kohl, if only you were born in his tribe.

The root of all evil is the love of money, says the Apostle Paul in Timothy. Well, who controls America’s money? Talmudic Jews, that’s who, hiding in the shadows. “One of the most impactful yet least discussed factors in history is that of debt slavery – it’s use as a tool of dominance and control, and a parasitic mass-siphoning of human energy, of mass power transfer. If we pull back to a sufficiently broad perspective, consider for a moment how deeply strange it is that in America we’re now simply born into a system in which we’re told we owe… Read more »

Yes.

If you don’t name the Synagogue of Satan, the Talmudic Jews behind every evil agenda, your message isn’t true, because you are lying, wittingly or unwittingly, by omission.

Follow the example of Christ, Paul, and the Apostles, who refused to be bullied by Jewish lies and intimidation and still publicly denounced Jewish treachery, all but John paying for it with their lives.

Viruses are a myth.

Coronavirus is a gigantic hoax created by parasites out of avarice.

The word “virus” comes from the word “poison” which is what it meant when invented.

Article on my website, 12/29/23

Since everyone of us reading this has been brainwashed by public schools and the media, it’s necessary to undo the brainwashing. James is the son of Paul Warburg, a Rothschild associate. The Rothschild, Warburg, and Schiff Jewish banking families all were very close in Germany over a century ago. Paul Warburg was the architect of the American Federal Reserve (started in 1913) . He also was the creator of the Council on Foreign Relations in 1920 (CFR) which still works hard to create a Jewish World Government. Paul Warburg’s brother was Felix Warburg, who married Frieda Schiff, the daughter of… Read more »

Friends don’t let friends watch Jewvision, watch movies, listen to the radio, read newspapers, put their children in public school, or have Twitter, Linked In, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, or accounts on any other social media site. The only site that doesn’t censor and allows criticism of Jewish wrongdoing is Gab. Even that has many disinformation accounts. Each of the entities mentioned in the first paragraph are controlled by Talmudic Jews who spread lies and disinformation daily. Not only are these sites and information sources a waste of time, but they spread lies that take a long time to unlearn. Reading… Read more »

How much should you study your Bible daily? It is stated by many reputable sources that Merie said she studied 2-3 hours every day. I once tried to do this with varying success, and I was a single man, reasonably well-off, with plenty of leisure time. If it was difficult for me, it’s reasonably certain it’s even more difficult for the man with a job, family, and preaching responsibilities. It’s even more difficult still for a woman with children, whose duties include her husband, her children, and the upkeep of the home, in that order. Sadly, many women have taken… Read more »

Improve your memory. Most people think their memory is either good or bad. They figure in some rare cases some people are geniuses or others take special exotic brain drugs to improve it temporarily. But this is wrong. You do not have a good or bad memory. Yes some people have a memory that is better than others. It is also true that some people have a higher capacity for memory than others. But here is the truth. The brain, like the body, functions like a muscle. The more you use it, the more skilled at using your brain you… Read more »

Where is all the animosity towards White people in America coming from? Why is it that when slavery has been around for thousands of years, America inherited it, and every race has enslaved others and been enslaved, that suddenly, the media and schools in the last century are teaching that Whites enslaving Blacks in America was the worst slavery EVAH!? Keep in mind that only 3% of the slaves taken from Africa by slave ships were brought to America and that slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean Sugar Plantations was far more brutal than American slavery. The first slave… Read more »

This is still the only form of religious discrimination in America today. “The Jews’ interference with the religion of others, and the Jews’ determination to wipe out of public life every sign of the predominant Christian character of the United States, is the only active form of religious intolerance in the country today.” ~ Henry Ford, The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem The Jews are also in charge of alcohol, gambling, pornography, prostitution, drugs, professional sports, and much more. Just noted that 114 million Americans watched the last Super Bowl. What a waste! That’s why no one is studying… Read more »

“If any young man expects, without faith, without thought, without study, without patient persevering labor, in the midst of and in spite of discouragement, to attain anything in this world that is worth attaining, he will simply wake up, by-and-by, and find that he has been playing the part of a fool.” MJ Savage This is the problem with the majority of American men. Hummingbird attention spans caused by watching Jewvision, Hollyweird, Pornography, and a lack of diligent research into history, the Bible, and the classics. It has been said it takes 10,000 hours of study to master a subject.… Read more »

Do you ever wonder why Hitler is hated so much by Americans when most have never read or heard any speeches by him and most have never heard persuasive arguments that the Holocaust either didn’t happen or was sensationalized? It’s because of the Jewish-controlled schools and media that brainwashed us all. Anyone who does the research quickly realizes that Jewish bankers controlled Churchill, FDR, De Gaulle, and Stalin. It’s unclear if Hitler defied the Jewish bankers or if he was their stooge, too. But it’s obvious that Jewish bankers were behind all the moral and economic woes in Germany before… Read more »

We hear about “racism,” “White supremacy,” “White Privilege,” and “White Guilt,” and “anti-semitism,” from the Jewish Schools and media every single day.

But, have you heard about Loxism?

How true. The most abused scripture in the Bible is the Matthew 7 “Judge not” passage. Glad DS taught many, including me, that this doesn’t mean not to judge at all; it means don’t judge others on what you are doing. Human nature is such that whenever it is corrected, its first instinct is to try to justify itself by finding the flaws of the accuser. Yet, many humans, like the Pharisees, strain at gnats and swallow camels. Fault finding and nitpicking are not good traits to possess. Yet some jump to conclusions about others, nearly always incorrect too, as… Read more »

Tens of thousands of pedophiles in Israel operating daily. The following is from a Jerusalem Post article. If the Jews themselves say something about other Jews, it’s true 99% of the time. Tens of thousands of pedophiles operate in Israel every year, leading to about 100,000 victims annually, according to an Israeli pedophile monitoring association. The Matzof Association, an organization that actively keeps track of reports on pedophiles in various media and centralizes the data monthly, states that in July alone, 22 cases of pedophilia were reported in Israel and brought to the attention of the media. The vast majority… Read more »

“The gold standard type of ruler for Satan’s kingdom is a woman, next best is a traitor, and third best is a young man without experience. Any of these three will allow Satan to come in and destroy. A woman in power reverses the roles set in place of God over man, justified by compassion but ending in destruction. A traitor will do anything for personal gain without respect to morality or justice. And a young man by his inexperience will be easily manipulated. Every western country has either a young man, a woman, or a traitor in power. This… Read more »

Indeed, this meme is so true. I’m happy I waited to marry, and I won’t be disappointed if I die single since a single person is married to God, who provides better than a human spouse ever can. “I am never less alone than when I am alone.” Matthew Henry How many sacrifice their souls trying to please others and their spouses? Also, if a man hasn’t mastered himself before marriage, he will have a difficult time in marriage. Even if he has mastered himself, if he’s in a church and nation where women are encouraged to rebel against God’s… Read more »

Now we see why the Zionist Jewish pawn Trump attacked Syria. Bashar al-Assad wasn’t buying the Jewish Holocaust hoax and was going off the reservation, and Israel couldn’t have that. Assad is right. The “Holocaust” is a Jewish lie to justify their wars of the past century and the creation of Israel, so Jewish criminals have someplace to run when they get caught. If you look up “ syrias assad holocaust hoax” on search engines, you’ll find hundreds of links to Jewish media excoriating Assad, as you’d expect. Looking it up on DuckDuckGo, owned by the Jew Weinberg, of the… Read more »

Blue bucket or green bucket.

Well over 90% of those identifying as Christians are badly deceived by Israel and the Jews. Just beginning the scintillating book by Michael Collins Piper, who was likely put to death for telling the truth, called “The New Babylon” Again, it isn’t available on Amazon, you have to find it on Archive. Perhaps it is possible to separate Jewish interests from Israeli interests, but the trick is yet to be turned. What touches Israel touches global Jewry, and vice versa. Purists and theoreticians may argue about the separation of church and state, Jews and Israelis, Judaism and Zionism, but in… Read more »

Roses in the night I believe.

The river overflows.